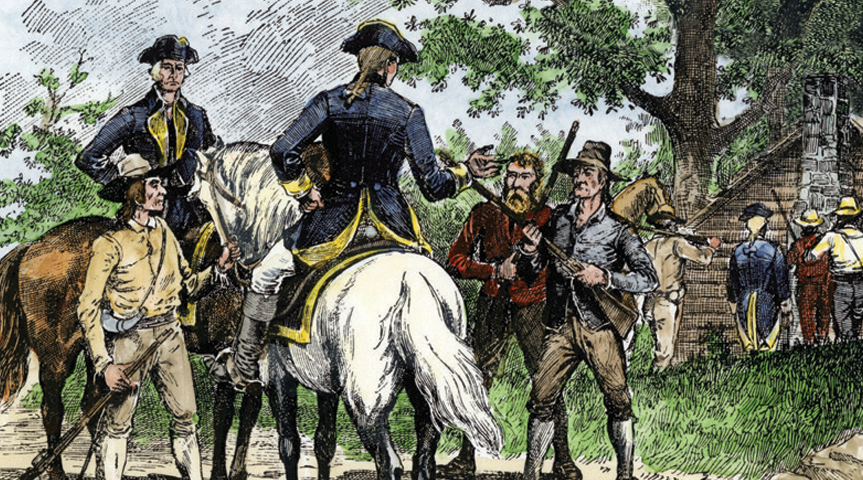

TRAVEL BACK TO 1794 AND WITNESS HISTORY UNFOLD, IN PREPARATION FOR THE CONTEMPORARY LONGRIFLE ASSOCIATION’S ANNUAL MEETING AND AUCTION.

Story by Frank JardimThis tale of historical fiction is written in celebration of the annual meeting of the Contemporary

Longrifle Association taking place August 8-10 at the Exhibit Hall of the Central Bank Center in Lexington, Kentucky. The CLA is an organization of artists, artisans, patrons and historians dedicated to the preservation of the skills and knowledge used to hand-make not just rifles, but all material objects of everyday early American life, just as they would have been made before 1830. That includes clothes, tomahawks, furniture, knives, tools and pottery, among other things, as well as the decorative arts of the period that enhanced the visual appeal of these objects.

While many CLA members are full-time artists and craftsmen who will have their best work exhibited for sale at the meeting, the organization truly welcomes all enthusiasts, skilled or not, who share their sincere interest andcuriosity about how things were really done in preindustrial times. Many instructional seminars are offered by individual CLA members throughout the year and whatever your interest (e.g., making guns, brain tanning deer hide, carving powder horns, embroidering with porcupine quills), you are sure to find a mentor to help you explore it.

For the past 28 years, the CLA has held a grand auction at the annual meeting of pieces donated by members, the proceeds from which go to support the organization and its programs. This year there are 30 exceptional lots up for bid, seven of which are featured in the prose and photographs of this story to illustrate how they could have been used. While the lead characters in this story are fictional, their circumstances are based on known facts and events and presented as they would have looked through their eyes as frontier Kentucky farmers at the height of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. I invite you to step back in time, 230 years ago, when the authority of the new American constitutional republic faced its first major internal challenge …

Rebellion after the new federal government was formed.

(NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)

OCTOBER MORNINGS ARE cold in Kentucky. Alexander Peale’s plans required he be on his way at least an hour before dawn. Dressed in his hunting shirt bound closed in the front with a woolen sash wrapped twice

snuggly around his waist and tied tight, he slipped his small bag ax and belt knife through it and slung his hunting bag and powder horn over his shoulder. Picking up his rifle scabbard, he headed for the door of the fortress-like two room log cabin his family of five called home. Three and a half years earlier, in the summer of 1790, he and his sons had felled a stand of oaks on the edge of their farm’s 5 cleared acres to build it with. The slimmest of the logs were 10 inches across when cleaved square. He felt West Point Army engineers could not have built a sturdier block house.

Like most Kentucky frontier farmers, the danger of Indian raids was never far from his mind, though he now had reason to hope that threat was diminished. Two months earlier, in August, he was among the 1,500

Kentucky Militia routing a coalition of hostile tribes on the Maumee River over 100 miles north. By order of President George Washington, the frontier state militias were called up for three-month tours of service outside their borders to support Federal troops fighting tribes at war with the United States.

Many living on the frontier, Peale included, were of the opinion that the new Federal government wasn’t doing enough to protect them from Indian raids and Federal troops who were deployed had an embarrassingly poor record of carrying the fight to the enemy in the Northwest over the last few years.

Their blundering emboldened the Indians and made the situation worse. The recent successful Battle of Fallen Timbers along the Maumee last August was different. Half the troops there were Kentucky militiamen under the command of their own officers.

Peale’s wife grabbed his arm as he began to unlatch the heavy cabin door, got on her tiptoes to press her cheek against his and said, “May God watch over you, dear husband … and you don’t go making it hard for Him!” He turned and winked at her as he hurried outside into the darkness. He had more than

the usual number of chores to attend to on and off the farm today, and while less troubled by Indian worries, his mind dwelled on the growing dissension between frontier farmers and the new Federal government over the despised whiskey tax.

The tax began in 1791 when the new Congress approved, and President Washington signed into law, the new constitutional republic’s first national tax, an excise tax on the production of spirits. In addition to actual commercial distilleries, most of which were in the East, just about every farmer was a part-time distiller. Congress expected the revenue to be sufficient to pay off the $75 million in war debt from the Revolution, a third of which had previously been a state burden until the new government took responsibility for their creditors.

Among the small farmers that populated the frontier, the tax was regarded as grossly unfair. Had

Kentucky been a state in 1791, her elected representatives to Congress would have argued vociferously against it. Resistance to the tax was most intense and violent in the western counties of Pennsylvania. Over the past three years, in addition to signing petitions and forming committees and other more gentlemanly means of opposition, tax collectors, and even tax advocates, had been beaten, tarred and feathered, attacked and besieged by organized mobs. Some people had lost their lives, while others suffered their

properties burned.

Last August, as a combined force of 3,000 Federal troops and federalized Kentucky Militia, Peale among them, marched toward a battle with the Indians, a mob of 7,000 Pennsylvania tax rebels, amounting to more than a third of the state’s western population, was marching on the Borough of Pittsburgh to protest the whiskey tax. President Washington was reported to have sought and received a declaration of rebellion from the Supreme Court allowing him to call up more state militias from Virginia, Eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey to form an army of nearly 13,000 to compel the rebels to obey the law. He temporarily took leave of his duties in Philadelphia, the first capital of the United States, to personally lead this force in the field. How the challenge had played out, Peale didn’t yet know. He was well apprised of recent events, having heard the matters discussed among the officers on the way to and from the Fallen Timbers fight, but back home his news came from the posted notices and private papers circulating in the county seat, which he visited only a few times a year. He respected Washington and believed the president would act with prudence to protect the new nation he had sacrificed so much of his life for. It was one thing to defy a tax collector and claim him a tyrant, and very much another to direct those accusations against the most beloved hero of the war for independence. If anyone could reel the tax rebels back in from the brink of a second revolution, it would be Washington.

WALKING TOWARD A fire’s glow under a lean-to near the barn, Peale reached into his pocket for the wool cap his wife had knit for him the previous fall. He put it on, pulling it over his ears against the chill. This morning his first task was to help his son pour off the spirits that had condensed overnight at their still. Working together by firelight, they sealed the clear liquid in small casks, their nostrils flaring from its powerful odor. As the morning sky was lightening, they hauled the casks to the barn in a cart and stacked them with the others. This eclipsing night’s work was the culmination of many weary nights tending the fire under their still. Finally, the last of their surplus corn harvest was converted to spirits. In Kentucky, and all along the frontier for that matter, specie, and even paper money, was scarce. Whiskey was used as currency.

Later in the week, they would load the casks in their wagon in preparation for a trip over the mountains. This was an annual ritual all along the Western frontier. Surplus grains were so bulky that there was no economical way for a frontier farmer to transport them over the mountains to Eastern markets and sell them at a profit. Distilled into spirits, those excess grains not only took up considerably less physical space, but they also sold for a higher price east of the mountains than they could be bartered for in the local market. East of the mountains was where the gold and silver currency circulated. What specie Peale and all the frontier farmers like him managed to save was in the main earned by transporting and selling their whiskey over the mountains.

Leaving his son to dismantle and stow away the still, Peale bid him goodbye, picked up his rifle scabbard,

and walked across his bare fields to the wagon trail leading through the forest toward the secondary road that eventually led to the county road and the county seat at Washington many miles away. Walking along the wagon trail he and his sons had widened from a footpath with axes and a two-man saw, Peale reflected on how much had happened since he mustered out of the Continental Army in 1783 when an eight-and-a-half-year-long state of war between the American states and Great Britain was finally, officially, ended with pen and paper by diplomats. At the time that he took his wife, sons and daughter west over the mountains to settle on the frontier, Kentucky was still part of Virginia, and the establishment of Mason County and the town of Washington, both named for great Virginia patriots, was years away. Now in 1794, Washington was the second biggest of the five or six towns in the new state of Kentucky. There were over 120 log dwellings populated by about 500 Christian souls.

Even a piedmont Virginian like Peale, growing up in sight of the Blue Ridge Mountains, knew Washington was no Williamsburg, but the settlement was an impressive accomplishment when you considered that most Indian tribes that previously resided on this land before the Revolution sided with the British against the newly United States and did their best to make Kentucky dark and bloody ground all over again.

The patriot settlers found no safety in old peace treaties negotiated with the King of England. They had to take up arms and fight the Indians off a second time. They were still fighting them now, for despite the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British continued to instigate Indian attacks from their forts along the Canadian border.

to Pennsylvania to defend against the taxing of

his whiskey. (CONTEMPORARY LONGRIFLE ASSOCIATION)

IT WAS ABOUT 10 in the morning when Peale arrived at his destination along the wooded county road. The

sunlight piercing the canopy of trees cast long shadows that dazzled the eye, creating a natural, if temporary, camouflage. This particular stretch of hard-packed earth road curved sharply along the foot of a knob on the south side. The lay of the land was such that a spot a dozen yards up the slope afforded direct observation of 100 feet of the road below just after the curve. “This is the spot,” he thought to himself. He drew his ax from his sash and began vigorously chopping off large limbs from young trees just inside the forest. He dragged the limbs into the road, piling them knee-high across the right side of it. As he worked, he noticed two figures with rifles watching him from the forest.

“Fine neighbors you are, letting me do all the work,” he shouted with mild annoyance in his voice. The two figures – one grey-bearded and older, and the other younger than he – emerged from the trees and

approached him with smiles. “Don’t be cross with us, laddie,” the older man said to him in a heavy Scottish burr. “You had the job near done when we came upon ya.” He pulled an engraved horn flask from his pocket, uncorked it, took a sip, and handed it to Peale. “You could stand to wet your whistle, laddie,” he said, “but don’t let the engraving get your hopes up. It’s just our corn liquor. I haven’t had a drop of proper Scotch whisky to taste since you patriots run the British off.” Peale took a small sip and looked at the flask. Embellished with a thistle, it read, “Ye Auld Scot Aged Fine Whisky.” He handed it back to the old man.

“I hope you brought more than this to sustain you,” Peale said. “If our spies at the court are correct, the gentleman we’re expecting should be coming down this road in a few hours. If not, we may be here all day. Either way, we should get in position.” Then he turned to lead them to the spot he’d scouted the day before on the high ground south of the road. From this position they were 50 yards from the pile of cut limbs with a clear view of it and the road all the way down to the curve.

They worked quickly to disguise their position so as to be completely invisible from the road and reviewed

their plans so each knew his role. Peale would fire the opening, and hopefully only, shot of the engagement. If that did not do the trick, his neighbors would shoot while he reloaded and they would keep shooting until the job was done.

As they settled into their hide for what might be a long wait, they talked to each other in whispers. Peale pulled his rifle from the scabbard, positioned it across his lap and sat facing the road. It was a fine, nearly new rifle he got from a North Carolinian three years earlier. The man came to Kentucky with high hopes and just enough luck to realize he wasn’t cut out for a frontier life before it killed him. In Raleigh, he wouldn’t need a rifle, so he said, and was happy to trade it against a horse.

The rifle’s stock was lighter and slimmer than long rifles made inColonial times and it was of smaller caliber, firing a half-inch ball faster and flatter than the old-style .54- and .58-caliber guns. Its thicker barrel was swamped to save weight and the furniture was made from iron that was darkened so it didn’t reflect light and reveal a man’s position in the woods like shiny brass sometimes did. It was fitted with a set trigger to enhance its long-range accuracy. Peale had found it easy to take big game at 200 yards with it. His reputation as a marksman was sealed in the summer of 1792 when he won the turkey shoot at the statehood celebration and then, just to show off, split a ball on an ax blade at 50 yards on the first try.

His neighbors, familiar with his fine rifle, took interest in its curious scabbard, the likes of which they had

never seen before. The younger man marveled at the realistic imprints of leaves that decorated it and asked if they were painted on. Peale explained that his daughter steamed them over the linen to imbed their pigments in the cloth, then sealed it with beeswax to make it weather-proof. The older man remarked that it would be nice to have a hunting shirt so disguised, especially in wet or cold weather. Peale and the younger man agreed.

PEALE EXCUSED HIMSELF from further quiet discussion to concentrate on continuously scanning the road for movement. He took his tobacco and folding knife from his pocket and cut himself a plug to chew to help pass the time. He would not have much time to pass. Minutes later, he spotted a mounted gentleman wearing an elegant blue coat with an unusually large and embellished matching cocked hat coming around the curve. Peale silently reached his right hand behind him to alert his companions. Their whispering

stopped and they picked up their rifles, cocked them, and leaned forward in their hide to observe the road and the mounted man moving along it at a trot. Peale cocked his rifle, set the hair trigger, and took aim.

When the rider noticed the pile of limbs partially obstructing the road, he slowed to a walking pace to investigate, just as Peale expected he would. The rider seemed nervous, looking rapidly right, left and behind, again and again. He finally stopped his horse 20 feet from the limbs, tipped back the front brim of his hat and began to scan the trees above him. Peale squeezed off a shot that took the gentleman’s fine blue hat off his head and split bark from a tree on the opposite side of the road.

The rifle’s report, the bullet’s crack and the flying bark startled the horse, which reared up and nearly threw the gentleman from his saddle. He struggled with the reins a long moment but succeeded in turning the animal back from whence they’d come. Two more shots rang out as he galloped toward the curve, clipping leaves from the tree branches that arched over the road. He was gone from sight before the leaves settled on the ground.

The trio remained alert in their position, now shrouded in black powder smoke, for a few minutes awaiting

further developments. The younger man broke the silence first. “I’ll bet you he resigns from his appointment by tomorrow at the latest.” “I would not take that bet,” Peale replied. “Nor I,” said the old man. “I guess the gentleman was more ambitious than smart. A man with good sense would be inclined to inquire why the chief revenue officer for the Kentucky district is unable to keep lucrative whiskey tax collector positions filled.”

“The vacancies suggest the position of exciseman is not as lucrative as the good Colonel John Marshall would have them believe,” Peale added, as he got up and returned his rifle to the scabbard. The three men abandoned their hide to make a brief search of the road before clearing the cut limbs away and heading home to their farms. Peale found the gentleman’s expensive cocked hat on the ground. The front point of the triangular folded brim was holed through both sides. He thought to himself, “Perfect shot.” ★

Editor’s note: For more information on the Contemporary Long Rifle Association, visit longrifle.com, and to learn more about the upcoming auction, go to contemporarylongriflefoundation.org/2024-fundraising-auction.