THE MILITIAMAN

Revolutionary War patriot comes alive in the annual creations of Contemporary Longrifle Association artisans

STORY BY FRANK JARDIM • PHOTOS BY DAVID WRIGHTThis October, the Contemporary Longrifle Association will hold its 25th anniversary annual meeting and art show in Lexington, Kentucky. Dedicated to preserving the artisanal skills of American craftsmen and -women spanning the colonial era through the start of the 1840s, the CLA encompasses artists working as gunmakers, horners, leather workers, weavers, embroiderers, clothing makers, blacksmiths and bladesmiths, potters, furniture makers and more, with virtually all professions, as well as the conventional decorative arts, represented among its membership. If it was made by skilled hands in America before 1840, there’s someone in the CLA who’s still doing it that way.

To commemorate the event and raise funds to support CLA programs, 47 artists have contributed their skills to create 23 unique individual objects and sets that will be auctioned at the show. As I examined some of those wonderfully executed auction lots, the authenticity of their details took my imagination back in time. With a little photographic help from CLA artist and respected painter David Wright, I offer you a glimpse of where nine particularly evocative pieces took me.

Just after his sixteenth birthday in June of 1776, Private Joshua Meade, the educated son of a successful surgeon, eagerly presented himself to fulfill his civic duty with the militia of Westchester County, New York. In the not-too-distant past, before his constitution failed him, Joshua’s father served in the militia as a lieutenant and some of the older men recalled him as a competent and dedicated officer.

On the morning of Joshua’s arrival, the regiment’s 459 men were preparing to make the day-long march down the Hudson River Valley to New York City to join General Washington’s Continental Army. Joshua kept his mouth shut, as his father advised, and did his best to follow orders.

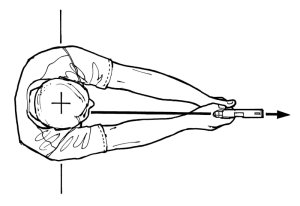

He had never marched before, or done any soldiering of any kind, but the other men assigned to his mess were quick to help him. They seemed to like him, and immediately bestowed upon him the obviously mock honor of carrying their iron cooking kettle. As the newcomer, and the youngest of his mess, he felt obliged to accept. He was strong and the extra weight was little bother to him at first, but that changed after the first mile. Various experiments finally revealed the cartage of the awkward pot was the least objectionable when it was harnessed in his leather blanket carrier and slung on his back over his knapsack with his untethered blanket stuffed inside.

The kettle notwithstanding, compared to other men in the regiment, he did not think himself over equipped. Some carried large swords, thick bedrolls and huge sacks whose seams were stretched to contain he-knew-not-what. To meet his militia duty requirements, Joshua had his father’s long 10-gauge fowler, a supply of cartridges loaded with lead balls instead of bird shot, 37 extra balls (all he could cast with the lead on hand the night before), a pound of gunpowder in an artisan-made, weather-tight, screw-top powder horn, a leather hunting bag instead of a cartridge box for his finished ammunition and small items to service his firelock, and a small belt axe instead of a sword. The axe was a more practical and useful tool than the sword, and, according to his father, a hand axe was about as useful in a fight as a sword would be in the hands of a man untrained in swordsmanship.

To this, he added a few more items. From the tanner, he bought a new lightweight, formed-leather canteen. It was more durable and easy to carry than a water skin, much more compact than a wooden canteen, and, he imagined, quieter to carry on patrol than the ones made of soldered sheet tin. On his belt he had a sharp and well balanced, bone-handled sheath knife, cleanly shaped and polished by a whitesmith.

It was small enough to eat with but still big enough to fight with. On his back he wore his father’s waterproof knapsack containing an extra set of small clothes and stockings, a hunk of soap, a tinderbox, the compass his father used as a militia officer, and six pounds of dried, salted pork, cheese and bread. From the weaver, his mother purchased for him a heavy wool blanket to keep him warm in the night and cold. Wool kept in the body’s warmth, even if it was wet. Before he’d taken on the kettle, he’d slung his blanket in its leather carrier on his back under the knapsack.

Joshua, on this first march to his first campaign, was in high spirits over the prospects of adventure that lay ahead and the pride he felt doing his part for their Glorious Cause of independence.

Two and a half months later, Joshua’s view of his prospects was bleak. He stood on the Brooklyn shore of the East River shivering and soaked to the skin in the night’s rain. Although he could barely see anything beyond a few rods, another 400 or so of his fellow Westchester militiamen from 16 to 50 were crowded mutely around him, equally wet and chilled. There were no fires to warm them.

The only light to see by came from a sliver of crescent moon. Two hours earlier, they were ordered out of their posts in the earthworks overlooking British engineers slowly digging their way toward them. Their sergeants and corporals ordered strict silence on the march from the fortifications as not to alert the British of their movements.

The lack of the usual conversation, jokes and even complaints left Joshua unexpectedly lonely. The loneliness and darkness added a sense of acute isolation to his present despair. His thoughts turned inward to recollections of the momentous battle of the preceding day. It was the largest military engagement in the history of the Americas.

GENERAL WASHINGTON STARTED with nearly 20,000 men, some of them newly organized into equally new Continental Army regiments, and the rest state and local militias like Joshua’s. Most had never been to war. Some had experience in frontier-style war against the Indians, and a small measure were veterans of Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill and the siege of Boston. But almost no one in America had fought a professional army in the European manner. On the water, Washington had but a handful of sloops operating as privateers.

The British arrived with an awe-inspiring fleet of unprecedented size. It included 10 fearsome ships-of-the-line with 100 or more heavy cannons each, 20 swift frigates, and hundreds of transport ships. Any one of the warships had the firepower to completely destroy New York City. Only nature could limit the scope of the Royal Navy’s operations on the water, and the present battleground was surrounded by navigable waterways!

The transports reportedly brought Howe as many as 32,000 men, all seasoned, disciplined troops … all with bayonets. There was nothing Joshua feared more than British bayonets. He wasn’t alone in that respect. Many of the militia carried their personal firelocks, and many of these guns were not even capable of mounting a bayonet, had they had any.

By noon the day before, the battle was done and the British had driven them from the field with bayonets, overwhelming General Sullivan’s troops so quickly, Joshua’s regiment was never even called to the line. Without realizing it, he said aloud to himself, “August 27th in the blessed year of our Lord 1776, we lost our Glorious Cause.”

At 50 years old, he was at the upper age limit for normal compulsory militia service. Most men under 40, and that was the majority of the militia, had never served beyond the four or five muster days a year legally required for drill and training. Oakley had actually fought in the provisional regiments raised by the colony to support British regulars, against the French and their Indian allies in the Seven Years War. At that time, Joshua was a babe at his mother’s breast. A lot had happened since that time to turn Old Man Oakley against his red-coated former comrades-in-arms.

Standing on the dark shore, Joshua became aware that men were moving around him and looked up. Silhouetted against the moonlight dancing on the water, he saw the black outline of barrel-chested Corporal Oakley pushing and pulling the shoulders of other human outlines to get them walking up the shoreline. Joshua, along with the rest, fell in with them.

It was a short distance to a ferry landing, where they boarded a small sloop docked there minutes before. Once as many as the vessel could carry were aboard, she efficiently and quietly pulled away and made sail for Manhattan Island, navigating without landmarks or light. To Joshua’s surprise, the vessel’s crew were the very same Massachusetts Marbleheaders of Colonel John Glover’s regiment who had manned a section of the Brooklyn Heights perimeter near his militia regiment during the day. These men were professional seamen and handled their commandeered boats with great skill and what looked to Joshua like perfect confidence and discipline. Aboard with nothing else to do, there was some whispering now among the militiamen, mostly of relief, but also troubling questions about their obvious defeat yesterday on Long Island. They were the same questions Joshua had asked himself since the British and their green-coated Hessian mercenaries turned the Continental Army’s left flank and drove Major General Sullivan’s troops from their main line of defense until only Brigadier General Alexander’s regiments on the far right held the line. The American retreat from their forward defenses was anything but orderly. It was more of a panicked rout than a retreat and he was shamed and terrified to see it.

In the early morning hours of the battle, it seemed from their breastworks on the Brooklyn Heights a few miles behind their forward positions, like the main British attack was focused on the right flank and Alexander’s men were at least holding their own. They drove off repeated frontal attacks, and when they realized the enemy was at their back, fought a valiant delaying action, allowing most of their line to retreat to the 2-mile-long defense perimeter on the Brooklyn Heights.

Joshua wondered how much of the Continental Army crossing the river tonight owed their escape to Alexander’s men on the right flank, who held their ground and kept up a vigorous fire. Reports were that the Maryland Continentals had fought nearly to the last man at the Old Stone House, repeatedly counterattacking so other troops could fall back to safety. There were few to tell the tale and General Alexander himself was feared captured or killed. Tonight, American morale was at its nadir.

“Have you still got your canteen, lad?” he asked. Joshua unslung his leather bottle and handed it to the old man. It was nearly empty. “Keep your canteen full, lad,” Oakley added, and poured the contents on the deck. Then he pulled a small bundle from under his coat and put it to the mouth of Joshua’s canteen.

“I obtained this restorative libation from the first mate,” he said. “How a Marblehead fisherman came to possess such a fine brandy, I dare not speculate, but I hope when its rightful owner discovers it missing, he will not curse us too harshly. I suspect it will do the Glorious Cause more good warming our bellies than his. Have a sip, lad.

“Thanks, Corporal Oakley,” Joshua said, and took a stout swig from the canteen. Then he took two more and reslung it around his chest. The brandy did as the old man promised and they sat in the near silence without speaking. Others on deck, as suggested by their snores, had probably fallen asleep, and what little quiet talking he still heard was terse commands to sailors. In short order, the brandy loosened Joshua’s tongue.

“Corporal Oakley? Are you awake?”

“I am now, lad,” he replied.

“I … I …,” he uttered with a shaky voice, “I’m worried our Glorious Cause is lost … that we can’t win against the British in a test of arms.”

“What makes you think that, lad?”

“Howe is a better general than Washington. The redcoats know how to fight and we don’t. The colonies are rotten with Tories spying for the enemy, sabotaging our plans and betraying us at every turn. We spent months building forts and earthworks that did us no good yesterday and our shore batteries are just as useless to impede the British fleet.

Had we stayed in Brooklyn Heights, sooner or later the wind and tide would favor them and they’d have sailed up and blasted us off the hilltop. Now we’re sailing to another island we can’t defend against their navy. We’ve slipped one trap by jumping into another. I fear the Continental Army is broken, and what’s left of it won’t last past the next time Washington is outfoxed. I fear that if I stay, I’ll be killed, and if I’m captured or surrender, I’ll be bayonetted to the trees like Sullivan’s men. If I go back home, I’ll be given up to the British by our Tory neighbors and hanged in due time.”

“Might as well fight then, lad,” the old man replied.

“But we can’t win.”

“You worry a lot for such a young fellow. All we need to do to win, lad … is not lose.”

“What do you call this disaster?!” Joshua asked, gesturing with his hands at the tired men all over the deck, dozing where they sat, firelocks embraced against their chests, hats pulled low on their heads.

“I’d call it a greater failure for General Howe than Washington. Howe is a soldier by profession. Washington is a planter. Howe could have cleared us all off the Brooklyn Heights by storm before supper yesterday.

He could have destroyed over half of the fighting strength of this new Continental Army. Had he killed or captured all 10,000 of us yesterday, instead of just a thousand, he probably would have killed any hope of our independence from England. But he did not, lad. Instead, thinking us trapped in our own breastworks with a river his fleet could control at our backs, he stopped his advance to lay siege. And here we are, lad.”

“All night we’ve been ferrying our soldiers away right under their noses to fight another day. We won’t tarry long on Manhattan either. Washington may not be half the General Howe is, but he’s no fool. Mark my words. We’ll outlast them because liberty is our Glorious Cause and to them this war is just another grab for colonial treasure. Those Hessian troops aren’t fighting for King George for love of their cousin. They’re mercenaries, and mercenaries don’t fight unless they are paid. I know you have not been paid a cent of the $6 you’re due monthly. I’ll venture it’s the same with most of the men in our patriot army. If they quit the field, it won’t be over coin.”

“How are you so sure we’ll outlast them?” Joshua asked. “Because, in one way or another, patriots have already been fighting for their liberty a dozen years, and we’ve not been dissuaded of its virtue yet, lad,” the old corporal answered. “The Declaration of Independence was forged slowly from a hundred insults to our rights as Englishmen. You’re too young to remember the crown’s first moves to put a boot on the neck of the colonies, but I remember the Stamp Act well.”

“I hope you are right,” Joshua replied, with more concern than challenge. He had no other response. As their sloop plied the East River toward the temporary safety of Manhattan, he thought hard about Oakley’s perspective on the rebellion. The more he thought, the more it seemed to ring true.

JOSHUA WAS FOUR years old when Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1764, but its infamy was still fresh in the minds of patriots. It required every legal document and everything printed, like books or pamphlets, to bear a royal tax stamp. To do this, royal tax collectors were commissioned. Because of open defiance from every colony, and in more than a few cases a sound thrashing at the hands of an angry patriot mob, within a year, every tax collector resigned his commission and the act was repealed.

The Stamp Act spawned the Sons of Liberty in Boston. Its credo, “No taxation without representation,” spread from colony to colony. In their defiance of the Stamp Act, Whig patriots, Old Man Oakley and Joshua’s father among them, took a stand against tyranny and demanded their rights as Englishmen be respected. Unfortunately, what followed showed that mother England saw them as colonial children unworthy of a voice in Parliament. In 1766, with not one legally elected member in the House of Lords or Common representing the three million English citizens in North America, Parliament voted it had the right to tax them as proof it had the right to tax them.

Parliament tried again with the Townsend Acts in 1767, taxing all imported British lead, glass, china, paper, paint and tea. Patriotic merchants in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New York defied the laws with coordinated boycotts of English imports. In Boston particularly, merchants with English goods in their stores ran the risk of becoming the target of patriot mobs who were not above destroying their property and treating the Tory shop owner to a new suit of tar and feathers.

Parliament resorted to musket and bayonet to enforce its authority in Boston and sent 2,000 British redcoats there to suppress the Sons of Liberty and protect loyalists.

Protests and defiance continued around the colonies, and in 1769, all the Townsend taxes, except the most lucrative one on tea, were rescinded. True to what Oakley had told him, that partial success didn’t much dissipate the passion of the American patriots. In Boston, violent confrontations between patriot mobs, Tories and British troops escalated. Events there finally lit the fuse to a powder keg of festering colonial grievances against England. Those events in Boston pushed young Joshua ever closer toward the belief that King George III was no paternalistic protector of the colonies.

In 1770, British troops fired on a patriot mob, killing and wounding 11 of them. The news of the Boston Massacre was for Joshua, and many of his Whig neighbors, a tipping point in their attitude towards royal authority in the colonies. But it was Parliament’s response to the Boston Tea Party in 1773 that convinced Joshua they had no future as free men under English rule.

When Boston Sons of Liberty destroyed a fortune in taxable tea in Boston Harbor, Parliament responded by passing the Coercive Acts to punish the city. The port was closed, local government suspended, crown officials placed above the law, and the private homes of citizens could be seized for the quartering of troops. Boston was essentially under military control. Rather than frighten the other colonies into compliance with Parliament’s edicts, the Coercive Acts unified their resolve to oppose British rule.

The more authority the crown sought to exert over the colonial patriots, the more they resisted until, finally, they could stand no more. Joshua had decided to take up the Glorious Cause of independence sooner than many, but he was young, a third-generation New Yorker, and had no ties to England. He realized for others, a break could be harder, and some would simply remain unwaveringly loyal to the crown for personal or business reasons uniquely their own. The signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 would be a bitter pill for loyalists to swallow.

A MONTH AND a half before the battle, on July 9, Joshua’s regiment was among a few thousand soldiers assembled with arms for parade on the New York City commons. General Washington was present, as were all the locals who could crowd in to watch. After the parade, the full text of the Declaration of Independence was read to them. At the conclusion, the troops let out three cheers. After they were dismissed, there was no joyous revelry. Joshua walked to the piers at the southern foot of the city, where he could see the huge British invasion fleet anchored miles down the Hudson River between the western shore of Long Island and the eastern shore of Staten Island. It was the largest ever deployed to North America and its combined masts made it appear that forest had grown up where a river had once been.

It was a sobering sight. With the Declaration of Independence, Joshua knew there was no going back. Regardless of what the Tories or the fence-sitters thought, there were enough patriots to create a new Continental Congress to rule them, a new Continental Army to defend the united colonies, and finally enough to declare themselves a new and independent free nation. Soon he would be called on to back up those words on the battlefield. As he sat near the southern docks, he carved “1776” into the lid of his father’s compass.

ON THE DIMLY moonlit East River, Joshua’s sloop closed in on the Manhattan piers. He noticed two other sloops glide silently past them heading back toward the Brooklyn shore. Minutes later, their sloop docked as expertly and quietly as it had embarked. In 10 minutes, they were all ashore and it was pulling away again into the night for the next load of soldiers. The Westchester militiamen formed into small groups and made their way to their quarters. Joshua’s path took him past Bowling Green, where a big, gilded-lead equestrian statue of King George III once stood. Right after hearing the Declaration of Independence read, the locals gathered and pulled the statue down with ropes to melt down for bullets.

Joshua trudged ahead wearily under the waterlogged weight of his clothes and gear with his big fowler cradled against his chest by both tired arms. Passing the empty pedestal, he smiled and thought, “Our Glorious Cause makes patriots when they are needed.”