Suppressed Revolver

Was the Preferred Weapon for the U.S. “Tunnel Rats” while Hunting the Việt Cộng

Since World War II, America’s elite forces have used quiet firearms for missions where it pays to be silent. Sound suppressors—commonly referred known as silencers—remain in service today. What many don’t know is that U.S. commandos once carried revolvers with special cartridges designed to muffle gunshots.

In the 1960s, the AAI Corporation developed the cartridges for the U.S. Army’s and Navy’s rifles, pistols and shotguns. The U.S. Army Special Forces and Rangers tested the unique ammunition in Vietnam.

While they offered many advantages, AAI’s products failed to win any widespread acceptance in the halls of the Pentagon. The rounds were expensive and ineffective at moderate ranges.

According to a 1968 Army report on silencers, “Throughout the history of firearms, gun noise has been of considerable concern to the military.” “To the enemy, gun noise reveals presence and, often, the location of the shooter, thus resulting in a counter attack.”

To better understand how a suppressor works. In most modern firearms, the sound of the gunshot comes primarily from bottled-up gases escaping as the bullet leaves the barrel—like uncorking a bottle of champagne. A sound suppressor helps muffle the bang by trapping these fumes.

But even with these devices, the gunshot is never entirely undetectable.

In the early 1960s, Army weapon designers looked at alternatives that would completely eliminate the sound of the propellant exploding. They came up with the so-called “piston cartridges”.

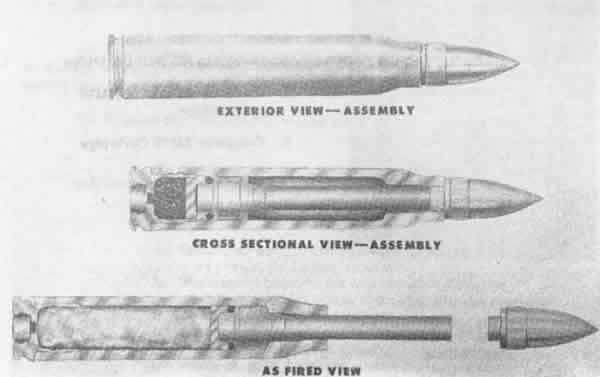

How this special cartridge works

A normal cartridge contains a casing—which contains gunpowder—and a bullet wedged into an opening at the top. When the propellant detonates, the bullet explosively detaches from the casing, and goes flying through the barrel toward its target.

In a piston cartridge, the case is completely sealed. A plunger transfers the force of the explosion to the slug—like the cue ball striking another in a game of pool.

A gun shooting these types of rounds produces no muzzle flash or smoke, either.

By 1962, the Army had piston rounds available for .30-caliber rifles and .38-caliber revolvers. The ground combat branch’s Special Forces sections also planned to develop a new weapon to go along with the ammunition.

This special firearm was envisioned to provide “escape detection, terrorize the enemy, taking out enemy patrol, snipers, sabotage, reconnaissance and assassination,” according to a report from the Army’s Chief of Ordnance.

The weapon designers also felt this firearm could silently take out sensitive vehicles and gear like aircraft, missiles, radar dishes and electronics.

Above is the artists conception of this relatively crude hand cannon that looks equal parts revolver and submachine gun. The concept features a folding butt-stock and simple iron sights.

Commandos could use the special firearms to “eliminate sentries, guards, guard dogs, military and civilian personnel and collaborators,” the technical document suggests.

With all the speculation, in the end, this new revolver was used in the tunnels during the Vietnam war to hunt for the Việt Cộngs.

The Việt Cộng dug elaborate subterranean networks to hide guerrilla fighters and supplies from American firepower.

Soldiers who volunteered to scour these amazingly complex tunnels couldn’t carry full-size M-16 rifles with them through the narrow entry points. M-1911 pistols were their only means of defense.

However, the tight passages amplified the sound of gunshots. These U.S. “tunnel rats” could quickly go deaf from firing their pistols at enemy fighters.

To try and save the soldiers’ ears, Army commanders scrounged up silenced .22-caliber handguns. The Limited War Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland also sent suppressed .38 caliber revolvers—but without any special piston rounds.

This gave the AAI Corporation a chance to to build a dedicated “tunnel weapon.”

As it turns out, the AAI’s modified gun came in as a .44 and .38-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver. The weapon fired piston cartridges loaded with 15 steel pellets, making it a miniature shotgun. The Army quickly sent 10 of the unique revolvers and almost 1,000 rounds of ammunition to South Vietnam for testing.

While intended for tunnel-scouting soldiers, the 23rd and 25th Infantry Divisions both handed the weapons over to their Ranger units. Special Forces soldiers reportedly got some of the guns, as well.

Units using it had successes as reported by the U.S. Army, “The tunnel weapon was found to be ideally suited for ambushes.” As originally expected, the elite troops used their silent guns on various occasions to ambush and kill enemy officers.

At the same time, AAI was offering similar ammunition to the Navy SEALs. The sailing branch purchased a stock of silent full-size, 12-gauge shells for their own experiments.

“The only sound heard when firing the silent shotgun shell was the click of the shotgun’s firing pin,” writes noted SEAL historian Kevin Dockery in Special Warfare Special Weapons. “Though the … shell was not completely silent, it made a weapon firing it very hard to hear and effectively unnoticeable.”

But the ammunition had serious restrictions. Silencers can slow bullets to varying degrees, piston cartridges launch their projectiles at even lower velocities.

How slow? AAI’s tunnel weapon—eventually renamed the Special Purpose Quiet Revolver—was useless at distances greater than 25 feet.

“There were several occasions in which the tunnel weapon failed to incapacitate an enemy soldier after he was hit from 10 feet away,” Army evaluators reported.

“Another instances, the first round struck a large leather pocketbook, filled with papers, that was being carried across the officer’s chest,” the shooter reported. “The second round struck his stomach, knocked him over, but failed to kill him.”

“The high cost was not considered balanced by the usefulness of the round as other suppressed weapons were becoming available, and the project was shelved,” Dockery stated.

The Navy didn’t buy any more rounds from AAI, either. In 1973, the Army followed suit and canned their revolver program. “No further development was planned,” progress reports from Aberdeen declare. “Several weapons and some ammunition will be available … if a special need arises.”

Today, American commandos regularly use more technologically advanced suppressed guns, but don’t have a pressing need for the complicated piston cartridges.

Photos from SmallArmsoftheWorld.com, Pinterest, U.S. Army, Wikipedia

Sources: Joseph Trevithick , SEAL historian Kevin Dockery, MilitaryVideo.com, War is Boring