A Brief History Of Taps

Story by Danielle Breteau

The story and origin of the bugle call known as “Taps” can be found in many versions, including the legend of a son fighting on the opposing side of the Civil War from his father. This legend depicts a Northern boy who was killed fighting for the Confederates. His father, Robert Ellicombe, a captain in the Union Army, came upon his son’s body and found the notes to Taps in the pocket of the dead boy’s uniform. When Union General Daniel Sickles heard the story, he had the notes played at the boy’s funeral. While this very short version of the legend is deeply meaningful to anyone who reads it, historical documents show us another story.

According to tactics manuals of the time, as well as letters on record, Taps was a modified version of a previously known Scottish “tattoo.” The term tattoo was originally a form of military music. The tattoo titled “Extinguish Lights,” meaning lights out at the end of the day, was played each night for the troops even before the Civil War and was borrowed from the French. This is documented in Silas Casey’s (1801-82) tactics manual, among others of the time. The song was even referred to as the “go to sleep” song by the soldiers.

To look back even further into history you will find that the word tattoo was most likely derived from an early 17th century Dutch phrase “doe den tap toe,” meaning, “turn off the tap.” This signal, sounded by drummers or trumpeters, instructed innkeepers near military garrisons to stop serving beer and for soldiers to return to their barracks.

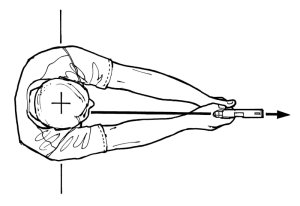

Union General Daniel Butterfield (Third Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the Potomac) is credited with writing Taps as we know it today, and according to a series of letters, Taps was a modified version of this previously known and used tattoo. One of the letters on records depicts how General Butterfield used his version in battle:

“I had composed a call for my brigade, to precede any calls, indicating that such were calls, or orders, for my brigade alone. This was of very great use and effect on the march and in battle. It enabled me to cause my whole command, at times, in march, covering over a mile on the road, all to halt instantly, and lie down, and all arise and start at the same moment; to forward in line of battle, simultaneously, in action and charge etc. It saves fatigue. The men rather liked their call, and began to sing my name to it. It was three notes and a catch. I cannot write a note of music, but have gotten my wife to write it from my whistling it to her, and enclose it. The men would sing, ‘Dan, Dan, Dan, Butterfield, Butterfield’ to the notes when a call came. Later, in battle, or in some trying circumstances or an advance of difficulties, they sometimes sang, ‘Damn, Damn, Damn, Butterfield, Butterfield.’”

If you read further, General Butterfield mentions he solicited the help of someone who could actually write music, although he could also play the bugle, as that was an important duty of his position. Butterfield lengthened some notes and shortened others until he achieved the sound that he felt was appropriate. It is said that buglers from surrounding camps, after hearing Butterfield’s bugle calls, would come and ask for the tune, which he freely shared. ASJ

Editor’s note: There are many thoughts on the origin of Taps. I would like to personally thank Jari A. Villanueva, who is a bugler and bugle historian. A graduate of the Peabody Conservatory and Kent State University, Villanueva was the curator for the Taps Bugle Exhibit at Arlington National Cemetery from 1999-2002. He has been a member of the United States Air Force Band since 1985 and is considered the country’s foremost authority on the bugle call of Taps.