TFB Book Review: The ‘Broomhandle’ Mauser by Jonathan Ferguson

The C96 ‘Broomhandle’ Mauser is certainly one of the most iconic self-loading handguns of the First World War. Osprey Publications has recently published a title about the C96, written by Jonathan Ferguson, Curator of Firearms at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, UK. For those not familiar with the Weapon Series from Osprey Publications, they are written to give a well organized and explained, yet easy to read, description of a particular small arm. The books are generally 80 pages in length and supplemented with artwork and high-quality photographs. The Weapon Series of books aren’t meant to be a definitive guide, but instead more of a survey for those wishing to expand their knowledge in regards to any particular small arm.

Ferguson begins his final chapter with this quote, “Overall it has to be said that the Mauser pales in comparison with later pistol designs and would be unsuitable for today’s various military, police, and civilian needs. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that in 1896 there was simply nothing in its class to touch its firepower, reliability, and accuracy potential.” Summed up in two sentences is the story of the C96 from its debut in 1896 to the end of production in the 1930s. Although it was technologically advanced at the time, it quickly became outclassed by Browning and Luger designs.

But the Mauser is unique in its historical trajectory. Similar to many iconic firearms, it was beloved and loathed by criminal, soldier, cop, and civilian alike. And for that reason, Ferguson’s book really stands out in taking the reader on this Mauser journey.

This particular paragraph was interesting about the use of the Mauser C96 during the Sydney Street Siege, giving very eerie parallels to what we often see today with media discussing civilian small arms ownership.

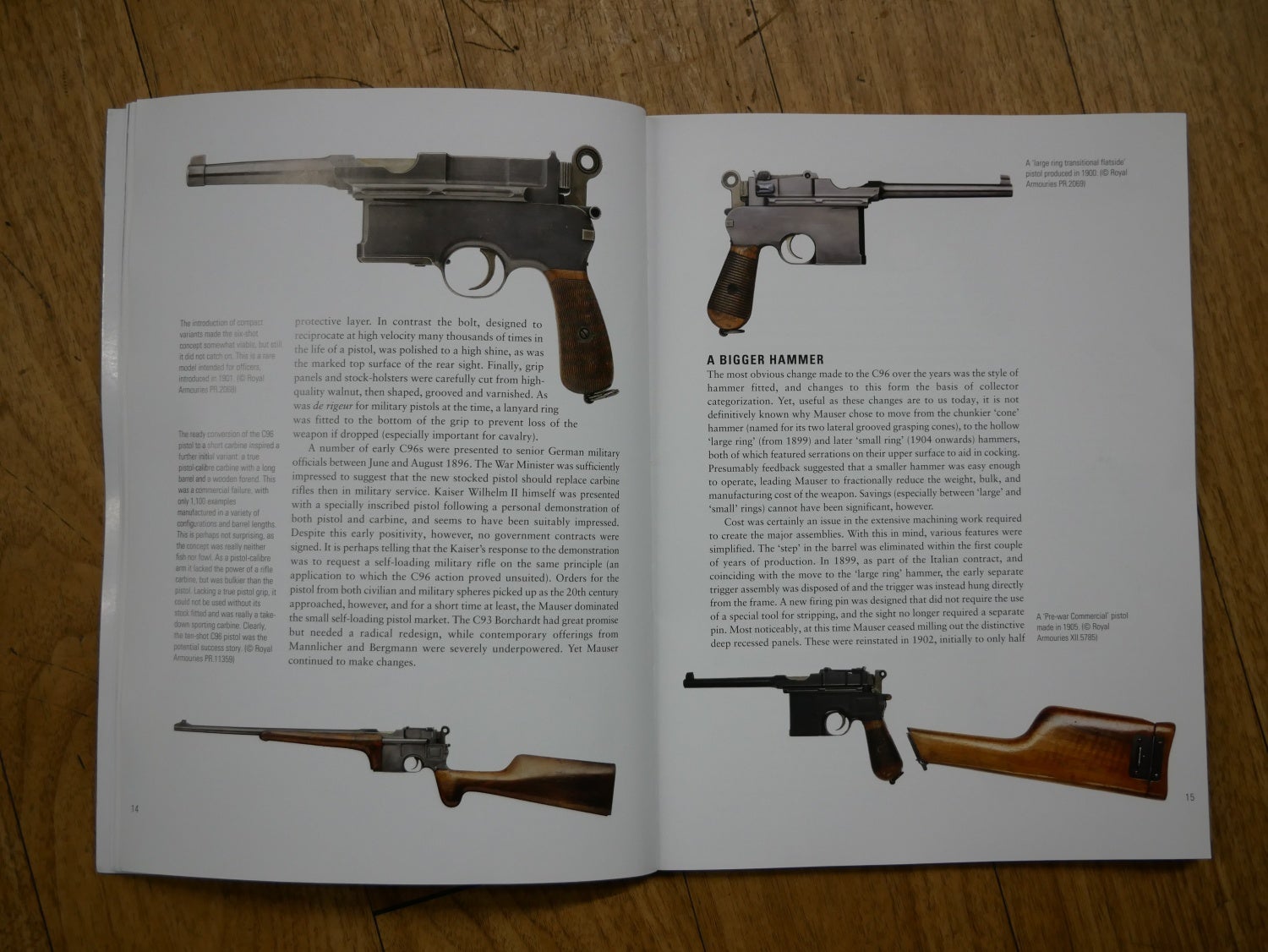

One important point about Jonathon Ferguson’s position at the Royal Armouries is that he was able to use dozens of C96s that exist in the National Firearms Centre reference collection as images throughout the book. It is this access that really allows readers to get to know the design changes throughout the different variants that were produced.

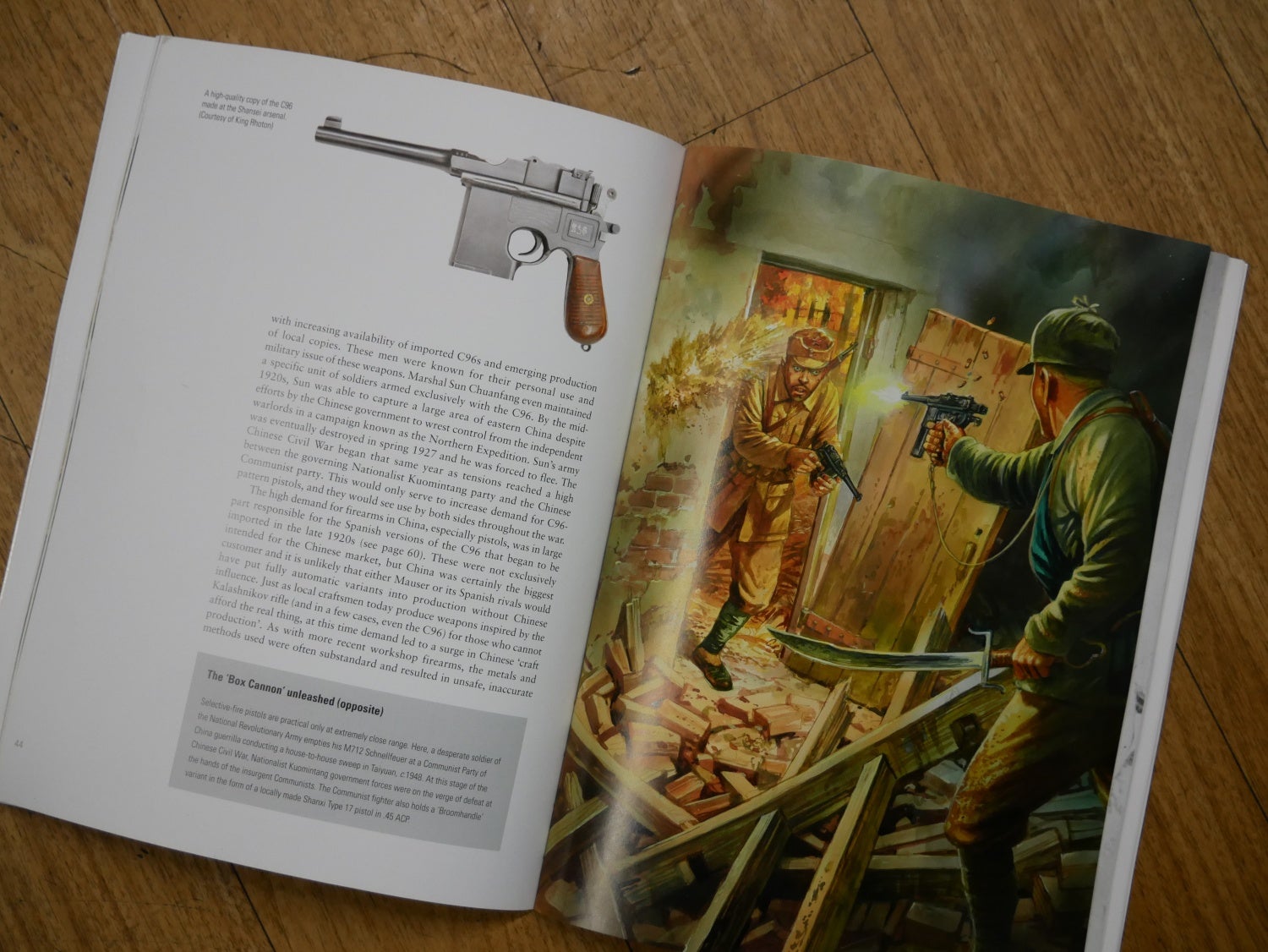

The artwork is trying to give a reader of a colored sense of the circumstances that these old firearms were actually used in. Note that both the Chinese Communist and his Nationalist Army foe have C96s or at least a variant thereof (possibly produced in China), illustrating the widespread popularity of the C96 on both sides of the Chinese Civil War.

Content

The book begins with the development of the C96 with the operational requirement for a self-loading handgun. An interesting fact here is that the Mauser team specifically designed the handgun to not have a single pin in the operating mechanism holding the trigger and hammer together.

Ferguson discusses partial acceptance by some elements within the German Army, mostly as an alternative to a bolt action carbine in use by cavalry. Later on, the C96 would have to bow to the Luger as a substitute standard handgun. He then goes into describing the different versions and iterations as Mauser worked on different safety and hammer designs and even carbine versions. He ends the initial chapter by discussing the end of the Mauser C96 in the 1930s after over one million were made.

The remaining chapters discuss the C96 throughout the world and this is what I really like about it. He discusses Mausers that were extensively used by Chinese warlords, rebels in Ireland and Armenia, police in South America that continued to use Brommhandles into the 1960s and 70s and even adventurers around the world that relied on the C96 for defense in the bush. He also discusses the different copies of the C96 from Spain to China, both licensed and unlicensed. Interestingly, Chinese Norinco was still producing a domestic copy of the C96 into the 1970s as the Type 80 for paratroopers. It ended up as a failure and was never really issued.

It was really neat reading this page about the dedicated carbine version of the C96, seeing that perhaps 1,100 were ever made, and then to actually hold the real deal in the Las Vegas Antique Gun Show the next week.

What’s in a Name?

As with many iconic small arms, names for them often vary from locality to locality. Ferguson makes specific mention of this throughout the book and even points out that Mauser as a company didn’t even have a standard nomenclature for the handgun throughout its production life. In China it was called the “Box Cannon”, in Ireland “Peter the Painter”, some British called it a “Bolo” for its use by a number of Communists/“Bolsheviks” after the First World War, among many other both official and unofficial terms. And of course throughout much of the English speaking world, the “Broomhandle”.

Room for Improvement

As always, I want to point out a few bits that the book could possibly have done better on. One point I would have really liked to see is in the conclusion that Ferguson could have discussed the current collector market of the C96 today, or even the subsequent reproductions and possible fakes out there. He spends time covering the image of the C69 in various Hollywood films which is important, but I would have liked at least a paragraph or two on the collector market today. Also, on page 64 there is a mismatched caption to photograph which should show the internal rate reducing mechanism of an Astra C96 copy, but instead only shows the external handgun. And this just because of my own interests but in one photo caption, Ferguson mentions that Ottoman C96s had their rear sights marked in ‘Farsi’ numerals. This is incorrect as Ottoman Turkish would have used Arabic numerals instead of Farsi ones.

Ferguson uses an inset to describe the different forms of safety catches, which is very important to identifying a C96 from afar. Early safeties were found to be quite insufficient through British experiences during the Boer War.

Conclusion

If you are a collector of German handguns, you could probably duplicate the written contents of this book yourself many times over so it wouldn’t be for you. But, if you are a student of the First World War or early 20th Century small arms, want to get a gift for someone who is, or are simply more curious about this German steampunk handgun, then I would absolutely recommend this Osprey Weapons Series book for you.

The ‘Broomhandle’ Mauser is available from Amazon for $13.59 in the United States.